It had been a little over three years since ABATE of Wisconsin lodged a formal complaint over the murder of Roger Lyons by the Milwaukee police. Since September, 1977, we had engaged in a campaign to seek justice for Lyons. Although a distraction from our motorcycle related endeavors, including safety issues, MORP funding and keeping an eye on the EPA noise restrictions, we felt it was necessary to continue looking for answers to who killed Lyons. The ABATE board of directors granted permission to business agent Tony “Pan” Sanfelipo and board member Nick Campanelli to explore membership in several coalitions that were forming to deal with police brutality issues. ABATE gained needed notoriety in the motorcycle community, and not so desired notoriety with the Milwaukee police and FBI.

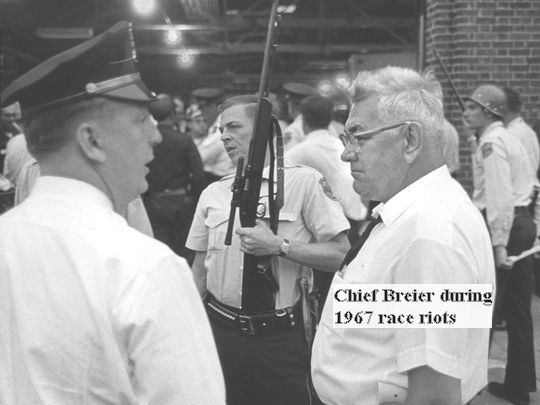

Milwaukee, in the ‘60s and ‘70s, was not a hospitable place to be if you belonged to certain classes of citizens, namely minorities, civil activists, feminists, or bikers. Police Chief Harold Breier had a particular disdain for those groups and stood by his officers against any claims of misconduct or brutality. The chief made it known that he remembered the two anti-helmet rallies held in “his” city prior to repeal, and he didn’t extend any courtesy to the protesting bikers.

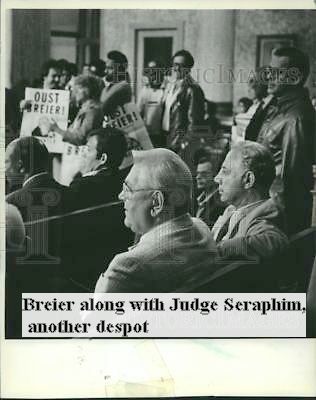

Sanfelipo and Campanelli joined a group called the Committee for a Democratic Police. It’s function, along with the Coalition to Oust Breier, was to force the Common Council or Mayor to remove Breier from office. At that time, the chief’s reign was for a lifetime; until he died or retired. We needed to fix that along with getting rid of Breier.

You have to understand that if you fit into one of the classes of persona non grata, it was dangerous to speak or act out against the police or Breier. Many in the community were afraid of him and his so-called goon squads. To be clear, not all police were bad, but certain factions within the department were given carte blanche authority to act, with full support of the chief. Many in Milwaukee felt Breier had to be removed in order to restore confidence in the police. ABATE had not dealt with such community actions outside of motorcycle issues before. We joined the ranks of many groups fighting for justice, including the black community and various activist organizations. Some of those affiliations were with groups we never thought we’d be aligned with due to differing political views, but this movement was solely based on addressing the concerns of police brutality and the despotic rule of Harold Breier. Interestingly, while ABATE was welcomed by most groups in the black community, the All African Revolutionary People’s Party criticized the inclusion of whites on the various steering committees. Their platform was not as non-violent as others.

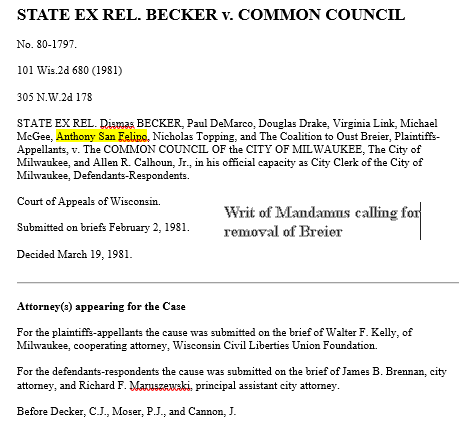

Our committee filed a Writ of Mandamus, which is a command issued to a private or municipal corporation, demanding a certain action. In this case, we petitioned the Common Council of Milwaukee to remove Breier from office. Boldly signing among members of the Wisconsin Civil Liberties Union and Coalition to Oust Breier was Sanfelipo, representing the Committee for a Democratic Police and ABATE.

The Court of Appeals decided on March 19, 1981, that the trial court was correct in quashing the resolution citing “no-confidence,” because it was administrative and the neither the Common Council or the Mayor could act on it.

Then, in July, 1981, a young black man who was painting an apartment near downtown Milwaukee, took a break from the summer heat and decided to walk to a store on 24th and Wisconsin Ave. for some refreshment. It was after 10 PM, and a call about a rape came over the police communications, and three tactical squad officers stopped Ernest Lacy for questioning. In those days, a young black man walking at night was almost always suspected of doing something. Lacy suffered from Schizophrenia and was diagnosed as psychotic. According to family members, he was also very afraid of the police, as were many young black men at the time. When confronted, according to police, he resisted and struggled to run away. He was taken to the ground, and just like Lyons, he never uttered another word. Witnesses said police handcuffed him behind his back while kneeling between his shoulder blades. That’s a typical police maneuver to gain control of a suspect. Then, according to witnesses, they raised his cuffed arms over his head violently. That was not a typical maneuver.

Because we were already involved with a movement to address police brutality after Lyons was killed, we immediately became interested in Lacy. The similarities were uncanny. Lacy was innocent of the rape (they arrested someone else later), according to police he resisted, as they said Lyons had, and Deputy Medical Examiner, Warren Hill, and Chief Medical Examiner, Chesley Erwin, presided at both inquests. Just as they reported to Lyon’s family that he probably died of a heart attack (instead of the blunt trauma and sixth degree concussion he actually suffered), police told Lacy’s family that he probably died of fright. In fact, the ruling at the inquest was that Lacy died of an “interruption of oxygen flow to the brain, due to pressure applied to his chest and a nerve in his neck.” Of course, Erwin said he couldn’t tell exactly what caused the interruption of oxygen or death. Does anyone doubt it was the kneeling on Lacy’s back and the raising of his cuffed arms above his head?

Just as in the Lyon’s case, Breier stood by his officers and denied they did anything wrong. One thing we learned was that Breier always backed his officers, and everyone expected his denial would be automatic, no matter the circumstances. That’s why most of his officers liked him. What we had to remember was, on the other hand, we could not automatically find fault with the police and fall into the trap that the media would paint us as malcontents, with an expected and automatic response contrary to the chief’s response. We needed proof, although we suspected the police, regardless. Since 1972, there were 267 complaints of police brutality reported (not sure how many were unreported due to fear) and 154 of those cases were dismissed.

The black community in Milwaukee was much better prepared to go on the offensive on such matters then the biker community was. The Lyon’s case was the first formal entry into that dark world of brutality, and it seemed only bikers were interested in finding justice for Lyons. The black community, on the other hand, had been dealing with segregation, discrimination and brutality since before the civil war. As recent as 1967, there were major riots across America, including Milwaukee. Activists fought hard to gain civil rights, including the infamous marches across the 16th Street Viaduct in Milwaukee, led by Father Groppi, a white civil rights leader who worked with a local group known as the Commandos, appearing very similar to the Black Panthers, but whose platform was based on non-violence as taught by Dr. Martin Luther King. Not that the Commandos would turn the other cheek though, if push came to shove.

The Lacy case gained national attention, with over 700 newspaper articles about his death and the aftermath. Unlike the biker community, which was small in 1981 Milwaukee, the black community consisted of many groups and organizations, including the NAACP. After the medical inquest jury recommended the three officers involved with Lacy be charged with homicide by reckless conduct, and the paddy wagon officers be charged with misconduct in public office and failure to render aid, there was a short-lived feeling that there might be justice for Lacy. Breier refused to suspend or fire any officers until the Police and Fire Commission ordered him to do so.

As Breier continued to defend his officers and policies, news came out about the 1958 shooting of Daniel Bell, a young black man who fled from officers. Police claimed Bell was armed with a knife. More than twenty years later, one of the two officers involved confessed that his partner planted the knife on Bell after the shooting. That revelation did huge damage to the police department’s already tarnished reputation, while further fueling the fires of contempt and protest in the black community.

Several large protest marches were conducted by different groups seeking justice for Lacy, the largest one marching down Wisconsin Ave. from 27th Street to the Police Administration Building plaza. It was during the planning of this huge march that Sanfelipo was contacted by the Milwaukee Commandos. His name came up because a local activist in the black community, Michael McGee, knew Sanfelipo from the Committee for a Democratic Police. McGee, and local activist Howard Fuller, were leaders in the Justice for Lacy movement. Tony was summoned to the Commandos headquarters on 5th and North Ave. He was accompanied by Denny “Dortz” Doherty, Sgt. At Arms for ABATE. It turned out that dozens of community and church groups had signed up to provide security for the large march coming up. The Commandos appreciated all the groups, but told ABATE that they didn’t put much faith or reliance on the groups if things got ugly. It was feared that infiltrators would join the ranks of the marchers and do something to cause the police to move in with riot gear, tear gas and batons swinging. That’s the last thing anybody wanted. It was decided that the Commandos would march at the front and along the flanks of the group, and that ABATE would provide bikers to march at the rear and along the rear flanks, keeping order and watching for suspicious people joining the marchers. We had about 50 ABATE and friends of ABATE join us in the march.

It all went down smooth, even though Breier rode in the back seat of an unmarked car, windows down, driving up and down the flanks of the marchers with his menacing stare. He failed to intimidate anyone and failed to entice any sort of disturbance that allowed him to unleash his troops. The only negative aspect of the whole march was that the media, in usual media fashion, embellished their report by writing that the Outlaws Milwaukee joined the march in support of the Commandos, which was untrue. Of course, reporting that a legislative organization like ABATE was supporting the community with assistance in the march just didn’t have the reader appeal that reporting a one- percent group of bikers was taking to the streets. One can only suspect that the reputation of the Outlaws in Milwaukee and the physical appearance of the military clad Commandos marching in unison would sell papers and scare citizens, directing attention away from the purpose of the march. Typical yellow journalism of the times.

What, if any, were the fruits of the coalition’s hard work? The Ernest Lacy Law was passed in 1983, making it a felony to delay rendering aid to an injured prisoner if death occurred. That law was later amended to downgrading the offense to a misdemeanor, and only if the death occurred as a result of “intentional failure to render aid,” which had to be proven.

Also, after Lyons was killed in 1977, ABATE’s membership in the Committee for a Democratic Police, was successful in getting legislation passed which limited the police chief term to four years. There was a massive campaign posting “Oust Breier” posters all over the city, along with ABATE members spreading matchbooks at bars that said “Fire Breier.” Unfortunately, Breier had a statutory lifetime tenure, and the new law did not affect him.

In 1984, through the work of the coalitions for justice for Lacy, the Fire and Police Commission was given authority to govern the policies of the police department through passage of SB56, severely limiting Breier’s power. He decided to retire in 1984 saying he would not serve under such restrictions. Finally, Breier was gone.

ABATE in the first twenty years of existence was involved in all kinds of issues, not particularly always motorcycle related, and we gained a lot of respect and attention in those early years. In just a short time, we would find ourselves again being called to the inner city, this time by members of a black motorcycle club, seeking our assistance.