42 years ago, a biker and friend of ABATE was murdered in Milwaukee. His death garnered nation-wide interest, and several motorcycle publications reported on the sinister circumstances surrounding this dark episode in our history.

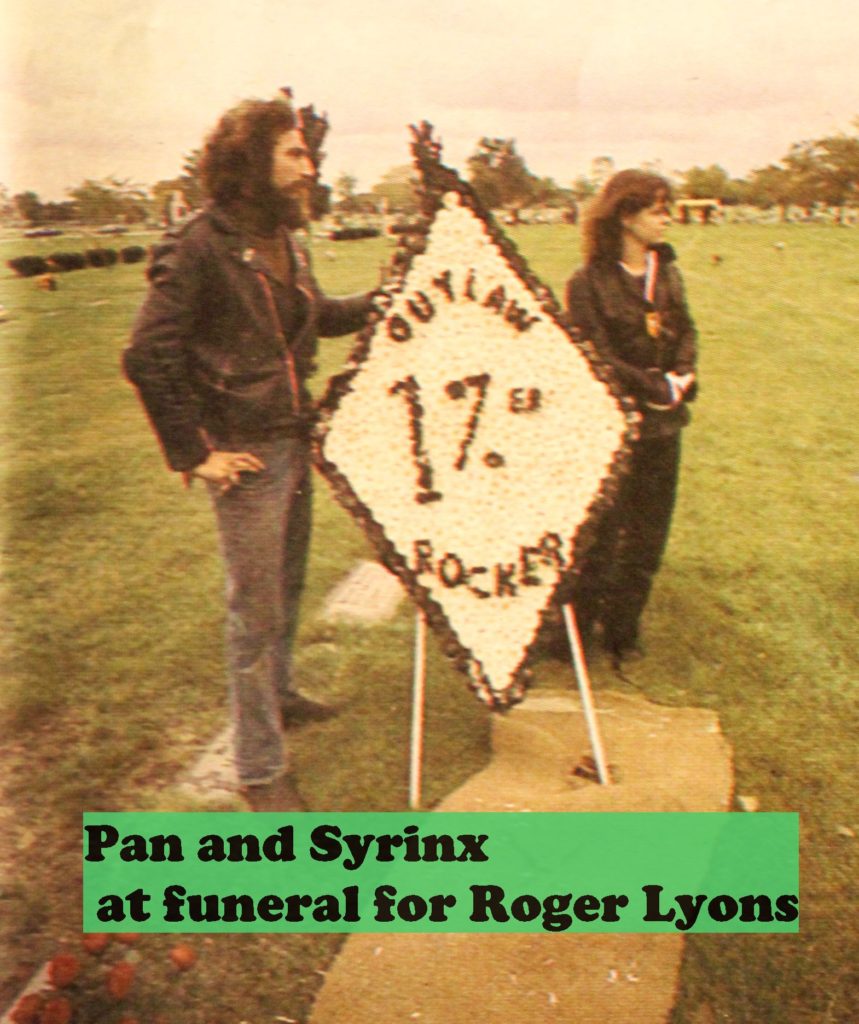

Roger, or “Rocker” as his club brothers called him, was a decorated Vietnam veteran. Shortly before his death, he joined the Outlaws Milwaukee MC. He lived on the north side of Milwaukee and most of his friends were ABATE members. His brother-in-law, Turtle, was ABATE’s first product director. His roommate was Dave Brunner, later to become a state director of ABATE. Because of his club affiliation, he wasn’t allowed to join any other organizations, but his heart was with ABATE and he attended most of the helmet rallies in Madison as well as signing his name to several petitions ABATE circulated in an attempt to gain sponsors for our repeal bills.

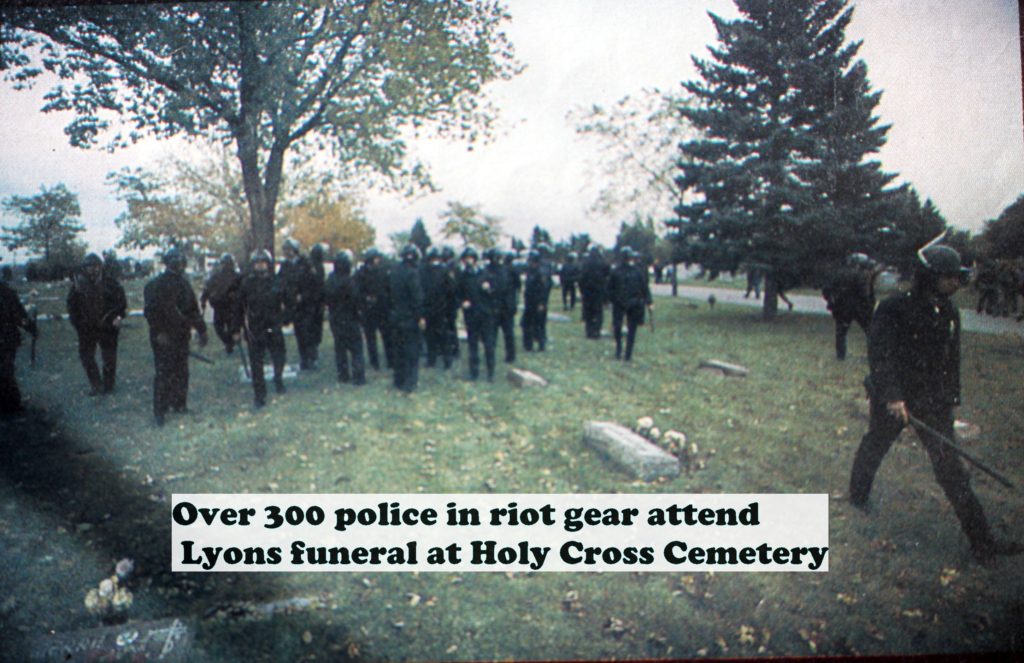

Milwaukee in the 1970s was not a hospitable place for motorcyclists. The police did not like us, and the only two helmet rallies in the city were near disastrous. In fact, for one rider named Dale Battersby, the second Milwaukee rally was disastrous. He was pulled off his motorcycle, beaten, arrested, and charged with attempting to kill a police officer with his motorcycle. This is the city Lyons grew up in and we all rode in. Profiling of bikers was a daily routine.

Our huge helmet rally on September 4 was over, and we were basking in the belief that our repeal bill would be voted on in the Assembly and we would be free to choose how we rode. Later that month, on September 30, 1977, Lyons joined friends at a north side bar named the Bus Stop Tavern. Events surrounding this incident started at approximately 10 P.M., according to witnesses. There was a brief scuffle around the pool table involving Lyons’ group and some men who were playing pool. Nothing much of a scuffle, some shoving and name calling, and then calm. The bartender feared a later escalation and called the police. They showed up 30 minutes later to a quiet atmosphere and asked what the problem was.

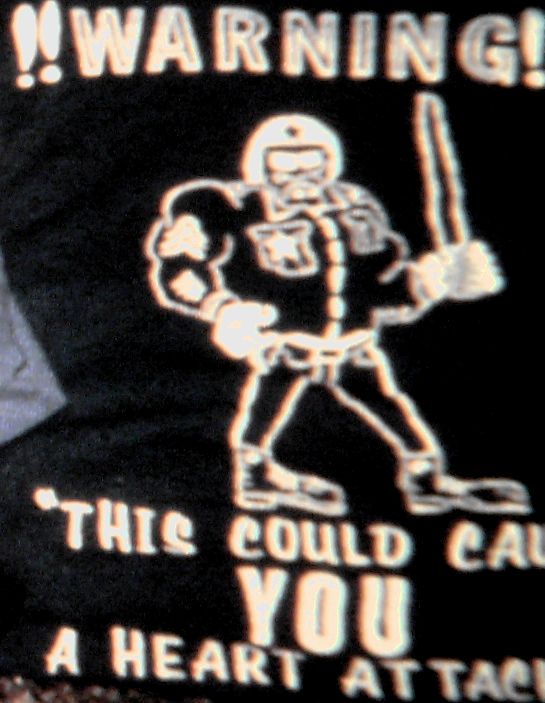

Those involved in the earlier scuffle were asked to leave, one by one, and according to police, Lyons refused and struck out at them. According to civilian witnesses, he stated he would leave as soon as he finished his drink (7-Up). He was told no, and after several attempts to bring his glass to his mouth, he was taken to the floor and all hell broke loose. He was dragged out of the bar, lifeless, and thrown onto the ground in the parking lot. Initial reports were that he apparently died from a heart attack. This was a futile attempt to cover up what really happened. To show contempt for this lie, we had T-shirts made showing a gestapo-style officer wielding a nightstick, with the words, “Warning, this could cause you a heart attack.” You can imagine how popular they were, and how police viewed those who wore them.

Why did ABATE get involved in this event? Besides the fact that Lyons was well-known in the Milwaukee ABATE circles, he was a fellow biker and our statement of purpose was to fight for the rights of all bikers in Wisconsin. We absolutely felt his constitutional and civil rights were violated.

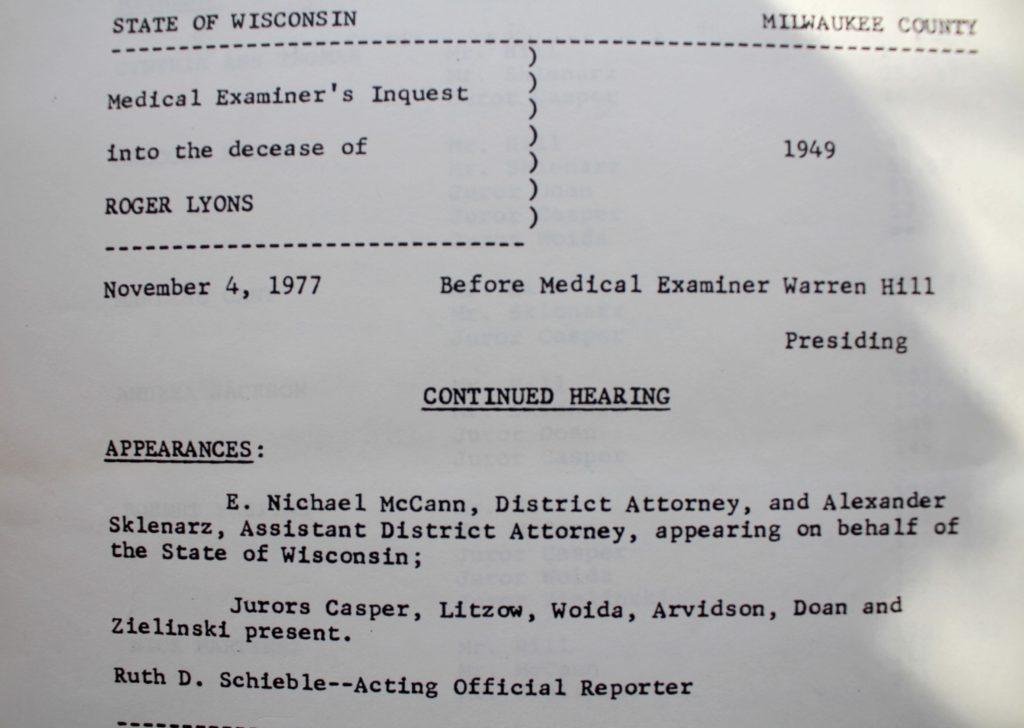

ABATE attended the entire Medical Examiner’s Inquest into Lyons’ death, which convened on November 4, 1977, and ended on November 11. After numerous witnesses testified, both civilian and police, as well as several pathologists who examined his body, the jury foreman read the verdict: “The cause of death was the result of brain swelling and concussion due to multiple blunt trauma injuries. The manner of death was the unlawful homicide by reckless conduct caused by a person or persons undetermined.”

During police testimony, it was suggested that Lyons may have been seriously injured during the brief scuffle, 30 minutes before police arrived. The jury had to deliberate on that theory. Of course, witnesses stated Lyons had no physical signs of injury before police arrived, and he acted normally after the scuffle in which no blows or kicking was noticed. Comparing that to the large group of officers who took him to the floor, dragged him to a dark corner, and surrounded him so no clear view was afforded anyone in the bar, it’s not hard to surmise that the serious injuries occurred then and not before police arrived. After being taken to the floor, he never uttered another word on this planet. Witnesses reported seeing nightsticks raining down on Lyons, but nobody could say who was swinging them or what they were hitting. This was a dance club, and the room was very dark, especially in the corner they dragged Lyons to.

The national attention this case attracted prompted Martin Jack Rosenblum, musician, poet, and curator at the Harley-Davidson Archives (forerunner to the HD-Museum) to write a song about Lyons. Also, Gary L. Kieffner, a history graduate student in the Ph.D. program at the University of Texas at El Paso, based a dissertation on the social and cultural changes of biker life in the twentieth century, pointing out that the Lyons murder became a sort of symbol for the denigration bikers received from the public. Kieffner was comparing similar motorcycle-related, street-level incidents in other regions of the country for his work, and the Lyons case represented the best documented case of the time. The details of this case were critical to his study and research of the intensity of societal conditions, while exploring the legal, juridical, and emotional dimensions during that decade.

In much simpler terms, ABATE was seeking justice for a fallen brother. There were many discrepancies during testimony at the inquest that cast a pall over the proceedings. We were met with scorn by many police attending the inquest each day as we worked our way to the front of the hearing room, right behind the family members. The media and others took photographs of us each day upon entering the hearing room, some for the news, others in an attempt to intimidate us. We just smiled and took our seats.

Comparing this to current day situations, consider the ramifications if police suspected of brutality were promoted during the investigation. What if one of the principal suspects were put in charge of the investigation? How would you react if you found that those police involved were gathered in a precinct room and compared notes, rehearsed their testimony, and conveniently forgot to bring requested items to the inquest? That’s exactly what happened in this case in 1977.

The report on the inquest is over 1,500 pages long, and to attempt to explain it would take way too much room in this history. But what is important to note is Lyons was left lying in the back of a patrol wagon for a long time before being transported to the seventh precinct station. The official time of death on the autopsy report is listed as 11:38 P.M. We suspect he died much earlier, while still at the Bus Stop Tavern. Police knew he was dead, therefore no rush to transport him, even though one of his companions who was arrested outside, and placed in the wagon before Lyons, was yelling that Lyons was hurt and needed medical attention.

Due to tireless efforts by private investigator, Ira B. Robins, in 1995, 18 years after his death, police officer Robert M. Schmidt came forward to say he was in the seventh precinct the night Lyons died. Robins helped break the case and set Lawrencia Bembenek free. She was accused of murdering her cop-husband’s former wife. If you want another inside look at the Milwaukee Police Department back in those days, please read her story, “Woman on Trial,” copyright 1992, by Lawrencia Bembenek, HarperCollins Publishing.

Officer Schmidt said he arrived just prior to the scheduled 11:00 P.M. roll call. At 11:10 P.M. he was told R 97 patrol wagon, which was already in the garage of the station, had a possible “dead prisoner” and he was asked to remove the man and convey him to the hospital. Schmidt refused because the prisoner should have been transported in the wagon he arrived in, according to protocol. Also, protocol demanded that an injured prisoner be transported immediately for medical attention, yet Lyons was left in the wagon at the Bus Stop for a prolonged time, then left in the wagon in the garage of the seventh precinct for at least 20 minutes or more. Those involved knew he was dead when he left the tavern, and getting stories straight and creating a timeline was essential in order to protect the guilty. Lyons was finally conveyed to Milwaukee County Hospital (now Froedtert), where he was pronounced at 11:38 P.M., but clearly he died much earlier than that.

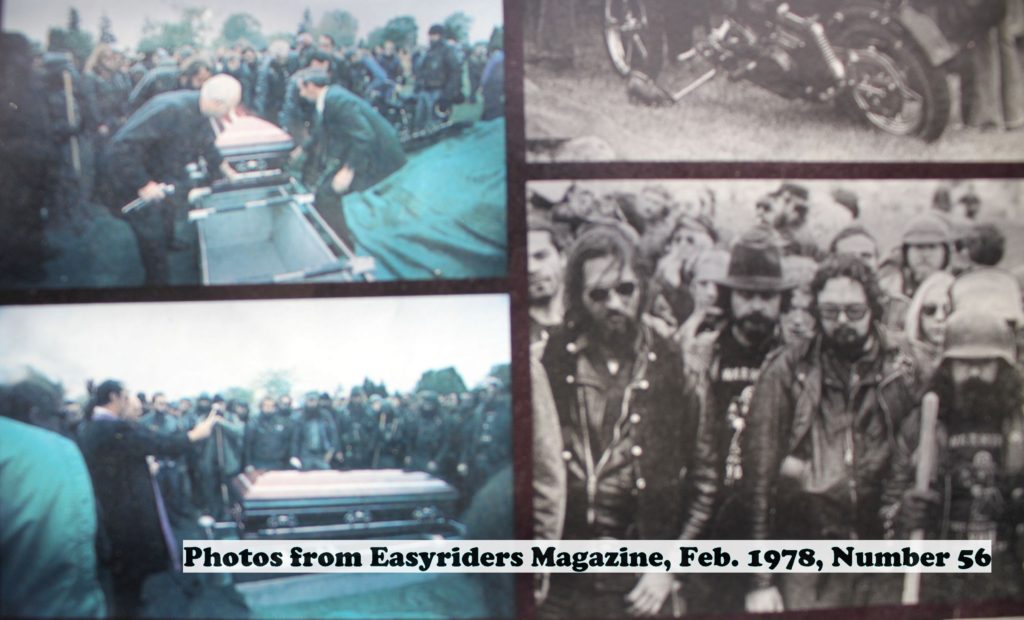

If you can find them, you can read more about the Lyons murder in Easyriders, February, 1978 #56 (original coverage), “Huge Biker Funeral,” by Billy Tinney and Woody. You can also read more about it in Biker Magazine, June 1992, #104, “Justice for Lyons: 14 Years Later,” by Pan.

An important development occurred as a result of the Lyons murder. ABATE joined a collective of community activist’s groups who were concerned about police brutality of minorities and rights leaders. During one of the Madison helmet rallies, Attorney Ken Hur called bikers “the new minority.” We testified at hearings and rallies and met with community leaders as we helped form the Committee for a Democratic Police. It was through the work of this committee that the term of the police chief of Milwaukee was changed from lifetime status to a fixed term. That was huge. We also received a lot of press after testifying at hearings concerned with police enforcement practices, and ABATE membership grew dramatically.

Roger Lyons was a man, a friend, a brother, and a biker. He did not deserve to die in the dirt and stale beer of a barroom floor. Standing up for Lyons made ABATE well-known as a viable force in the rights community. We would later be called upon to once again seek justice for a minority member who died while in police custody, eerily similar to the Lyons case.

As Kieffner pointed out in his dissertation, historians up to that time had not really concentrated on the non-commercial cultural history of motorcycling. In contrast, bikers have attracted a great deal of interest among cognate disciplines such as anthropology and sociology. Meanwhile, the Lyons murder remains a cold-case file in the dark catacombs of the Milwaukee police department.

In seeking justice, ABATE contacted the FBI, WGN TV, Chicago, for a segment on the Phil Donahue Show, CBS 60 minutes, Representative John Conyers, Jr., Committee on Civil Rights, and Senator Herb Kohl, Wisconsin. ABATE State Coordinator Tony Sanfelipo, and Free Riders MC president, Dave Zien, met with then Attorney General Jim Doyle for 45 minutes to discuss the case. His conclusion was nothing could be done without a “smoking gun.” In other words, one of the cops had to confess or tell on those guilty. Just like what happened in the Daniel Bell case, a 1958 murder of a young black man by police. Years later, one of the two officers in that case came forward to say his partner planted a weapon on Bell in order to justify his shooting of the man as he ran in fear of the police. He had committed no crime.

The Lyons’ case was reported in Biker Newsmagazine, Choppers, Easyriders, Motor Magazine (Germany), The Bugle (Milwaukee underground newspaper), and the Milwaukee Journal and Milwaukee Sentinel daily newspapers.

Lyons was a personification of everything that is going on today, with regard to profiling and extreme enforcement practices used against bikers. He is relevant because he symbolizes the dangers we face when confronted by a rogue cop, the prejudice of society, and the judgmental pontification of the media. As Marty Rosenblum wrote in his song about Lyons, “I Just Blame Everybody. Lyons “died on the barroom floor, he died in the street, he died in the paddy wagon, but we will not retreat, from fear and injustice, from secrets held until now…”

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA